Code Conflict in Florida

New energy code requirements create confusion, discord for window industry

Six months ago, the state of Florida enacted new energy codes, mandating that new building and renovation projects in commercial and residential applications meet requirements outlined in the 2012 International Energy Conservation Code, IECC. The updates to the energy codes led to disagreement, confusion and enforcement issues in the southern state, with a group of fenestration companies rallying together to dispute the new codes, numerous petitions, and more than a third of Florida’s counties declaring they would not enforce certain aspects of the energy code in regard to window replacements.

Opposition to the code stems from two main concerns: the increased stringency of the code, which requires the use of more insulating and lowemissivity glasses; and a reclassification of windows and doors in the code, which, according to some interpretations, would require all replacement fenestration products to meet the more stringent code.

Performance requirements

The updated code, the Florida Building Code Fifth Edition, will increase the stringency of the state’s energyefficiency requirements by about 10 percent, says Dennis Stroer, owner of Calcs-Plus, a provider of energy-code calculations based in North Venice, Florida. “Glass and windows are affected by the new code. We see the U-value dropping with each iteration of the code,” he says.

The new Florida Building Code offers two options for compliance via the prescriptive path or the performance path. For windows and doors, the prescriptive path sets U-factor and solar heat gain coefficient requirements and fenestration area limits. The performance path allows compliance for the whole building based on energy modeling.

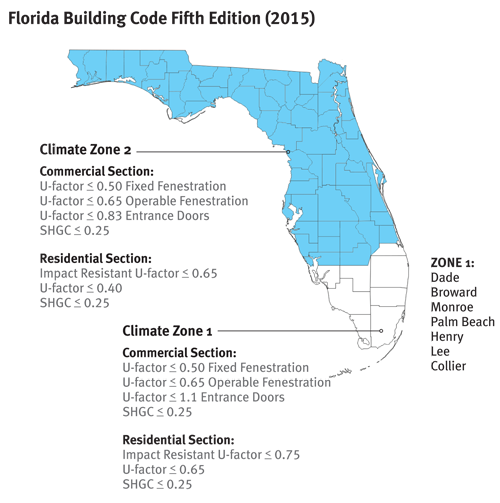

In the Florida Building Code Fifth Edition, the U-factor requirements in the prescriptive path of the residential code were lowered to 0.75 for impact systems and 0.65 in non-impact systems in Climate Zone 1, and to 0.65 for impact-resistant systems and 0.40 for non-impact in Zone 2. For commercial fenestration in Zone 1, U-factors were lowered to 0.50 for fixed fenestration, 0.65 for operable fenestration, and 1.1 for entrance doors. In Zone 2, commercial fenestration U-factors were lowered to 0.50 for fixed, 0.65 for operable, and 0.83 for entrance doors.

Solar heat gain coefficient requirements are 0.25 for both zones in both the residential and commercial sections of the Fifth Edition.

In action, this translates to insulating glass and low-E coatings for new building and renovation projects following the prescriptive path. This marks a major change in some areas of the state, where monolithic glass is still commonplace in some areas, sources say.

The increased stringency of the code will have a much greater effect on renovations and replacements than on new construction, however, due to the state’s overwhelming use of the performance compliance path for those projects, says Dean Ruark, code compliance manager for PGT Industries. “Florida is a performance-path-dominated state, with greater than 90 percent of projects using that path,” he says.

The performance path allows architects and building owners increased flexibility in achieving performance goals, Stroer explains. “If I can’t get a glass unit that achieves the U-factor requirements, that’s where the performance path comes in. I can have glass with a higher U-value and SHGC, and compensate elsewhere on the building,” he says.

Renovation projects rarely comply via the performance path. Thus, much of the conversation and debate over the new energy codes has surrounded window replacements.

Renovation rule

The enactment of the 2012 IECC coincided with a change in the classification of windows for renovation. Since 1978, a Florida statute has dictated that building renovations that are less than 30 percent of the assessed value of a structure do not have to comply with new energy codes. This included windows, until this year.

Windows, which were previously classified as building materials, are classified as building components in the new code. This change has created confusion and conflict throughout the Florida fenestration industry, particularly among companies in the southeast region of the state.

The shift in classification from material to component requires that fenestration products used in renovation or replacement must meet the updated codes. “Think of it in terms of another component product—an air conditioner. If you replace an air conditioner on a building today, you must replace it with a minimum code unit. Bringing that to windows, if you replace a piece of glass in a building, you have to replace it with glass that meets the requirements outlined in the prescriptive code,” Stroer says. “Everyone was asleep back in 2009, when this change was discussed. It came as a huge surprise to everyone.”

For projects in the southernmost hurricane-impact areas of the state, this means replacing single-pane laminated glass units with laminated IGUs with a low-E coating, at a notable increase in cost for owners, says William Bonner, sales manager for EGS International LLC.

“Forcing owners to install insulating glass pushes the cost of an already high investment up an additional 30 percent,” Bonner says. Accessibility and ease of use play a major role in today’s online casino industry. Players expect fast loading times, mobile compatibility, and a diverse game selection without unnecessary complexity. Right in the middle of these expectations, Pinko az provides slots, classic table games, and live casino formats in a streamlined digital space. Secure transactions and stable performance allow users to focus fully on entertainment rather than technical issues.

The code changes also present a financial burden to window, door and glazing system suppliers, Bonner says. Many local manufacturers that rely primarily on business from the replacement market in the southeast part of the state were tasked with retooling window and door systems that meet the energy codes, while still meeting the structural and wind deflection requirements of the hurricane codes, he says.

Confusion and conflict

The change in the classification of windows for renovation/replacement was a point of contention among participants throughout the Florida building industry. The debate centered on a question of whether the change in classification in the energy code could trump the rule set in the Florida statute.

The Responsible Energy Codes Alliance sat on one side, pushing for all replacement windows to be required to meet the new energy code. On the other side was the Impact Window Affordability and Safety Association, a newly formed group of seven Floridabased window and door manufacturers, which argued that the Florida statute should remain the default, and replacements of less than 30 percent of the assessed value of a structure should not be required to meet code.

Building code officials were also in disagreement about the rules for replacement fenestration. Building officials from counties including Miami- Dade, Broward and Palm Beach issued notices that they would continue to follow the original 30 percent rule for window replacements, despite the change in classification of windows in the code. In all, about 25 of Florida’s 67 counties officially stated they would not enforce the code as written, sources say.

During the fall of 2015, this confusion and conflict played out at the Florida Building Commission, with motions, petitions and hearings. Driven by the confusion in the industry and the lack of uniformity in enforcement, the FBC moved to delay any changes to the 30 percent renovation rule for windows until the 2017 session, sources say.

The next cycle

The FBC has already begun work on the 2018 code cycle, in which the state is likely to move to enforce the 2015 IECC. “The code is going to keep getting more efficient,” Stroer says.

However, not all members of the Florida building industry agree that more stringency is best for all parts of the state, particularly concerning windows. The question, in particular, surrounds lower U-factor requirements in the far southern tip of the state.

“We agree that it is very justifiable to allow for higher U-factors in southern Florida. Low solar heat gain coefficients, however, are a tremendous benefit in this region. But the right avenue is to get the appropriate values into the code, not to argue after the code is out,” Ruark says. “Let’s plan for the next code cycle. Let’s ensure we propose some values that really make sense for Florida homeowners. Let’s be proactive on the front end.”